πατησιωτης έγραψε: 31 Αύγ 2023, 07:58

Αρίστος έγραψε: 31 Αύγ 2023, 06:25

Με λιγα λογια ο πραγματικος φιλελευθερισμος ειναι κατα των ταυτοτητων ενω υπερ ειναι τα υπερσυγκεντρωτικα κρατη,

Και από πότε στην Ελλάδα ο "πατριωτικός χώρος" ήταν κατά της ύπαρξης ταυτοτήτων;η απάντηση είναι ποτέ.

Την τελευταία φορά με τον Χριστόδουλο η φασαρία έγινε όχι για το εάν θα υπάρχουν ταυτότητες αλλά για τον εάν ΘΑ ΑΦΑΙΡΕΘΕΊ μία πληροφορία από τις ταυτότητες,το θρήσκευμα.

Όλοι αυτοί που σήμερα παριστάνουν ότι ανησυχούν για τις πολλές πληροφορίες που θα έχει η ταυτότητα τότε ζητούσαν να υπάρχει μία ακόμη.Για τον λόγο αυτό όλοι καταλαβαίνουν ότι αυτά είναι προσχήματα και ο πραγματικός λόγος είναι κολλήματα με χαράγματα.

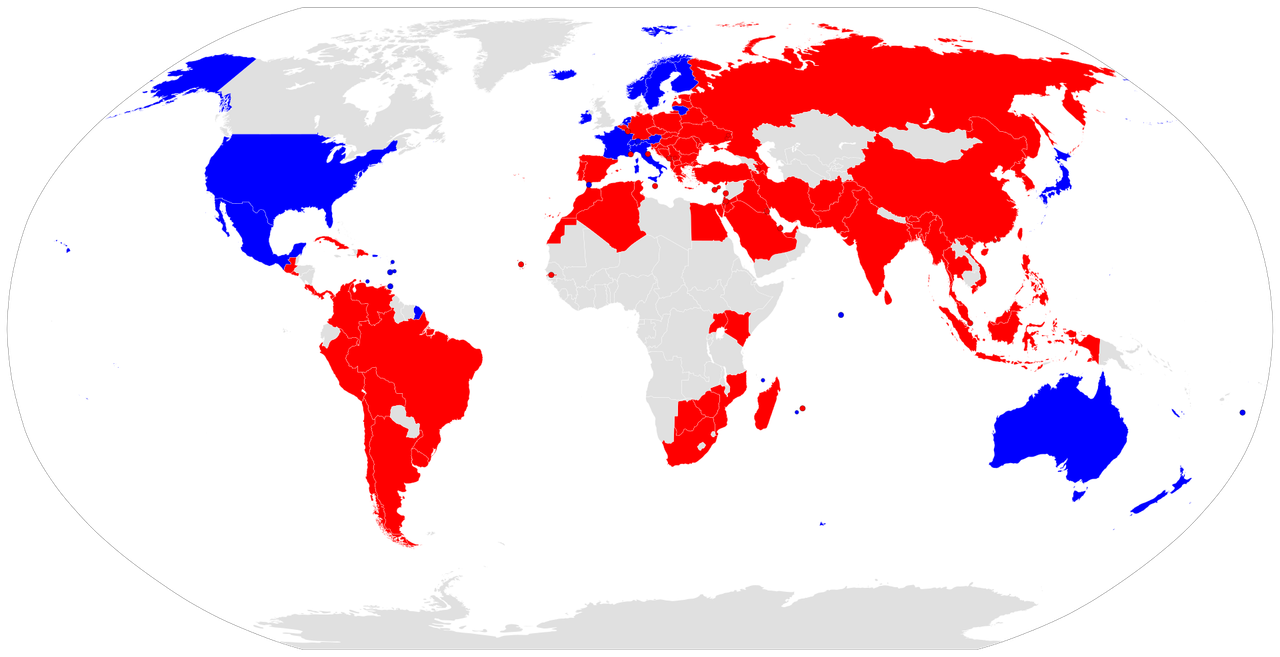

Το Aadhaar στην Ινδία είναι το μεγαλύτερο σύστημα βιομετρικών ταυτοτήτων στον κόσμο, μήπως έχεις πληροφορηθεί τί έχει συμβεί εκει;

https://pathwayscommission.bsg.ox.ac.uk ... xperiment/

All eyes on India’s biometric ID experiment

Apart from the questions on official data and evidence, India has been gripped by a post-implementation debate with the Supreme Court involving several critical rulings around issues of privacy, data security and the Aadhaar bill itself. The big question is whether India put the cart before the horse by implementing Aadhaar without fundamental regulations to deal with privacy and security of data. While Aadhaar has improved access for many, there are growing reports that the poorest and most marginalised families and communities face systems failures (e.g. labourers whose fingerprints have worn out) with no redressal process in place. In extreme cases, the denial of food subsidies has led to reports of deaths through starvation. In a perverse twist, the system has failed to help some of the most vulnerable people it had set out to protect and include. As a result, the debate has become highly polarised - should India continue or halt the program?

While many countries are apprehensive about the risks of creating a potential Big Brother state, India did not have a national debate before people’s private data was collected. The misuse of data by government has been very much a cause for concern in India, and indeed globally. Indeed, recent media reports highlighted the covert selling of information from the Aadhaar database. There have also been reports of various government departments openly publishing data from the Aadhaar database on their websites.

Trust, responsibility and ownership (who regulates the regulators, can government be trusted etc.?) are hotly debated. Answering such meta questions on privacy and data misuse – albeit long overdue - is crucial to the success of such a program, especially given that the personal information of a billion plus people is already in the hands of the state (and possibly also with others).

Aadhaar’s very constitutionality has also been questioned. Aadhaar was passed as a particular type of bill in India’s parliament (a ‘money bill’) that only requires a majority in the lower house to be passed as law. The ruling BJP party has a majority in this house and a lack of checks and balances from the second chamber has resulted in civil society activists challenging its legality in court.

A further misgiving about Aadhaar is that it had become a mandatory identifier- making it obligatory for all Indians to enrol until the Supreme Court stepped in and annulled any such instructions from the government. The government push for Aadhaar meant that private sector telecoms operators and banks sent repeat notifications to all its customers to link phone numbers and bank accounts to an Aadhaar ID number. If individuals did not comply, there was a threat that phone connections would be cut and bank accounts shut. Ethical questions were raised around such bullying in India’s democracy, and again reinforced concerns of an encroaching Big Brother state.

There is also real anger that the poor in India are being used as guinea pigs for this digital ID experiment – with critical systems failures. In some areas, Aadhaar was not only made mandatory but was the only mechanism for the poor to access subsidies and other welfare services including food entitlements. This has disastrous consequences if machines fail to authenticate individuals. Official government statistics suggest that the failure rate is 12%, though this is contentious. The real problem is for those people who face multiple ID failures; which this has led to a number of deaths, (though with little reliable data on the actual numbers).

A recent report by global development analytics firm IDinsight undertook a three-state survey across India to unpack some of the polarised debate with evidence. It highlights that although the numbers of people excluded from rations because of Aadhaar failure in the State of Rajasthan was significant (2.2%), more people were actually excluded for other reasons such as ration unavailability (6.5% or 3.7 million people).

https://www.accessnow.org/press-release ... ig-id-bad/

India’s Aadhaar proves Big ID is still a bad idea

Despite all the propaganda in favour of it, Aadhaar has had a disastrous impact on the lives of millions, as outlined in Access Now’s new report, Busting the dangerous myths of Big ID programs: cautionary lessons from India. It unpacks India’s experience over the past 10 years to help policy makers understand what is wrong with centralised, ubiquitous, data-heavy forms of digital identification, asking: why are they required? Read the full report, and the report snapshot.

“Aadhaar was catastrophic for human rights in India,” Ria Singh Sawhney, Asia Pacific Policy Fellow at Access Now. “We had multiple chances to stop, assess, and put human rights first, but we didn’t. And now we must collectively call on the governments around the world to not mirror our broken system.”

India’s experience with Aadhaar highlights how Big IDs — particularly when made mandatory for people to access public services — operate as a tool of exclusion, such as in Telangana, where a failed attempt to verify voters through Aadhaar left almost two million people disenfranchised. Yet Aadhaar continues to fly under the accountability radar. The lack of meaningful grievance redress mechanisms for a nation of 1.3 billion people has also been exposed, and the red lines laid down by the Indian Supreme Court are being openly flouted.